3 min read

The Cost of Market Power: When is Too Much Market Power Detrimental to a Market’s Global Competitiveness?

Antti Kämäräinen : October 30, 2015

How Institutional Landowners in the Northwest United States and Landowner Associations in Sweden Influence Global Competiveness

In the Northwest United States, the primary source of wood for building products and pulp and paper mills is the timberland owned by institutional investors (timberland investment management organizations and real estate investment trusts) and corporate landowners. Like landowners around the globe, the goal of these entities is to obtain the highest possible stumpage prices for their timber. In order to do so, they have traditionally matched log flow volume with demand. These sophisticated timberland owners are sure to meter out volume on an as needed basis. If you believe in the laws of supply and demand, then this practice should – all things being equal – keep log prices flush. Since abundant supply generally brings prices down, this strategy makes sense.

Or does it?

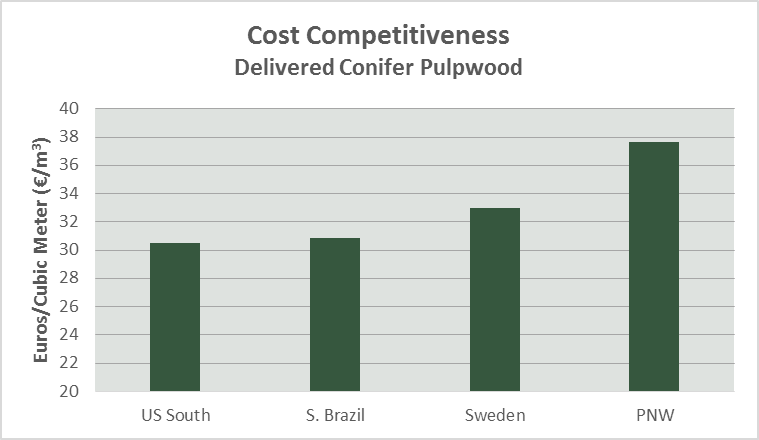

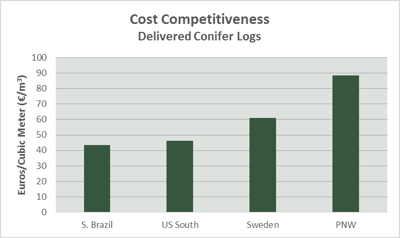

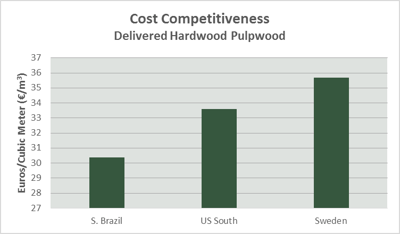

When it comes to a region being able to compete in end-products markets globally, this strategy could backfire. Looking at the relative cost of wood in markets around the world, we can see that global competition puts the Northwest United States at a decided disadvantage. Over time, as production capacity is rationalized on a global scale, the highest cost mills are the ones likely to close, and when that happens, markets for timber could potentially dry up altogether.

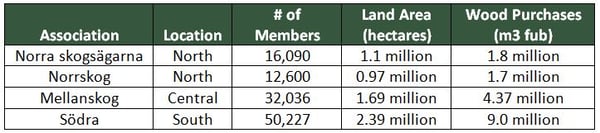

In Sweden, landowner associations have a similar effect on markets. These organizations were formed in the 1930s to help small private forest owners improve their ability to compete with large forest industries companies that dominated timber markets there. Their goal from the beginning was to promote the profitability of their members’ forests by:

- Acting as an intermediary in members' timber sales to the forest products industry

- Offering service and advice to members

- Lobbying on behalf of members

Today, there are four landowner associations, with more than 100,000 members, covering 6 million hectares and accounting for nearly 17 million m3 fub of the wood purchased in Sweden in 2014.

Things are especially concentrated in southern Sweden. With nearly 50 percent of market share in this region, more than half of the southern private forest owners are members of Södra. Exacerbating this dominance is the fact that Södra also owns several sawmills and a pulp mill. Not only does it have access to its members’ extensive forest resources, it is also capable of processing all incoming roundwood assortments. Södra is able to determine the wood price range, mainly because:

- It is an efficient saw milling company, the only company that is able to use its own by-products (sawmill residues can be transferred to the pulp mill).

- Profits can be distributed to members either in the form of higher stumpage prices or as earnings paid, so Södra can afford to offer better prices for wood than independent sawmills. Stumpage prices are intracompany transfer prices.

What this means is that independent mills are forced to pay higher prices than the market might otherwise bear for wood supply, and this makes them less competitive globally. (Interestingly, this phenomenon is not nearly as pronounced in northern or central Sweden as both markets have other large competitors.) While Södra and its members may benefit from this strategy in the short run, like the Northwest United States, when production capacity has to be rationalized globally at some point in the future, their high cost status could lead to closures, and closures will lead to lower prices and perhaps even loss of forest land.

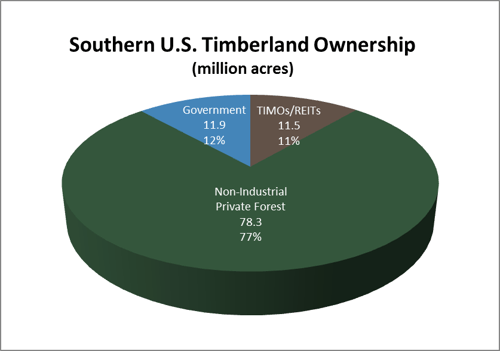

At the other extreme is the Southern United States. In the Southern United States, where 77 percent of the timberland is owned by non-industrial private forest owners, individuals make decisions about when to sell their timber and for how much. No one ownership group has the advantage in the market, and as a result, The Southern United States is much more competitive worldwide, with wood costs that are significantly lower than they are in markets like the Pacific Northwest and Sweden, where some players predominate and increase the risk for all regional producers and consumers.

The southern Brazil market, while not as fragmented as the US South, still has a very diverse softwood market with no one timberland owner or association controlling large wood volumes. In fact, manufacturers in southern Brazil export finished products to the US (as well as the EU and China). This is only possible because the southern United States is southern Brazil’s next lowest cost competitor.

Forest2Market is not arguing for lower stumpage prices. We are proponents of working forests and forest landowners who get compensated fairly. Rather, we are pointing out that when too much market power is placed in too few hands, true market forces of supply and demand are not allowed to work – often to the long-term detriment of local markets.