7 min read

Canadian Boreal Forest Agreement Survives Greenpeace Misinformation Campaign

Suz-Anne Kinney

:

March 27, 2013

Suz-Anne Kinney

:

March 27, 2013

Two and a half years after the groundbreaking agreement between Canadian forest products companies and environmental groups (ENGOs) to protect both the boreal forests of northern Canada and the caribou that live there, Greenpeace misrepresentations about Resolute Forest Products’ commitment to the agreement nearly derailed the work being done by both sides.

Greenpeace Misrepresents Resolute Forest Products’ Actions

December 6, 2012 – Greenpeace releases the results of their investigation to what it called “Violations of the Canadian Boreal Forest Agreement (CBFA) by Resolute Forest Products” and announces it is withdrawing from the agreement. Stephanie Goodwin, Greenpeace Canada forest coordinator said, “The Canadian Boreal Forest Agreement was a framework for cooperation whereby companies like Resolute Forest Products agreed to stay out of areas of important habitat. When the biggest logging company in the Boreal Forest goes back on its word to stay out of critical habitat, it signals the Agreement has broken down.”

Specifically, Greenpeace alleges that Resolute built five logging roads in the Montagnes Blanches forest in areas that were off limits for harvesting and road building (a map of the area marked with the alleged road building violations can be found at The Huffington Post Canada.) The organization also publishes a series of videos and photos that it says are tagged with GPS information that prove Resolute’s actions violate the CBFA.

December 14, 2012 – Resolute Forest Products’ President and CEO Richard Garneau sends a letter to customers addressing the allegations, calling them “false, based on erroneous, deceptive and misleading evidence, including GPS coordinates and video footage.” Specifically, Garneau points out that of the five reference points on Greenpeace’s map:

· Points 1 and 2 refer to roads that were “authorized areas for harvest and road building to maintain socio-economic activities while discussions are ongoing.” Resolute confirmed this fact with the external expert working for the CBFA and received confirmation that the specific GPS coordinates were for authorized roads.

· Points 3 and 4 refer to roads not constructed by Resolute, but by the Quebec Ministry of Natural Resources for the purpose of reforestation of a forest that burned in 2007.

· Point 5 refers to a site undergoing government planning and road building for a 2013-2014 scheduled harvest not by Resolute but by another forest products company that did not sign the CBFA.

In addition, Garneau points out the following fallacies in the video that Greenpeace posted:

· Images of activities taking place before the CBFA went into effect were used as examples of how Resolute violated the CBFA.

— An aerial image of a forest alleged by Greenpeace to have been “ravaged” by Resolute was actually harvested in 2000, well before the CBFA went into effect. The given GPS coordinates were incorrect, referring instead to a forest that burned in 2007.

— Another image identified an area that was harvested according to rules not in effect since 2003.

· Images are from burned forests, not those actually harvested.

— An image of forestry machinery plowing over trees and referred to as forest destruction was actually a machine used to prepare soil for reforestation. The particular tract shown is of a burned forest, where removing stems prior to reforestation is a best practice for safety purposes.

— Tracts shown look particularly devastated when they are the result of burns; buffers to waterways appear to have been ignored, as fire does not respect such boundaries.

January 16, 2013 – Greenpeace begins a solo campaign to halt logging operations in five Boreal forest areas: Broadback Valley, Montagnes Blanches, Kenogami-Ogoki, Trout Lake-Caribou and the Boreal Gem. In the publication that accompanied its announcement, Greenpeace once again took aim at Resolute Forest Products. In fact, Greenpeace singles Resolute out over and over in its publications and on its website, though without any specific examples that can be verified.

March 20, 2013 – Despite being informed of its errors one week after releasing the report, Greenpeace waits a full three and one-half months to recant its allegations against Resolute. The source of the errors, according to Greenpeace, was an “incomplete map that lacked a data layer.” The group’s statement read in part “Greenpeace has learned that the above-mentioned statements are incorrect and has removed any reference to the statements from all its materials. Greenpeace sincerely regrets its error.”

What’s Really Going On?

While it is true that any organization can make a mistake, this one seems particularly egregious.

Based on the course of events and Goodwin’s explanation, it appears Greenpeace would have accepted evidence that Resolute was violating the agreement, regardless of the validity of that evidence, because it is consistent with the group’s most closely held belief that forest products companies cannot be trusted.

What Greenpeace has proven, though, is that it cannot be trusted. Here are just a few reasons why:

· The explanation for the error is less than complete. How, for instance, can a missing layer of data be responsible for the characterization of a machine used for soil preparation prior to regeneration as a weapon of forest destruction? For an organization that spends thousands of hours and millions of dollars every year on issues related to forest ecology, it ought to have one person on the staff with knowledge of the best practices in reforestation methods and equipment.

· Not only did the organization not confirm the accuracy of its allegations prior to making them public (a rookie mistake for an organization packed with attorneys), but it also waited three and one-half months to right the wrong, leaving Resolute to deal with the negative publicity created by their false claims.

· According to The Globe and Mail, Stephanie Goodwin offered Greenpeace’s mea culpa as proof that the organization was willing to work with industry: “by listening to Resolute’s counterpoints,” said Goodwin, “Greenpeace is demonstrating that it takes opposing view from companies seriously.” Instead of using this as opportunity to offer a sincere apology to Resolute, Goodwin uses it as an opportunity to congratulate her own organization.

· Goodwin’s characterization of the evidence offered by Garneau as “counterpoints,” as if he is offering an argument instead of scientifically verifiable facts, is just as disingenuous as Greenpeace’s using trumped up charges against Resolute as an excuse for reneging on their commitment to the CBFA.

· Greenpeace has refused to rejoin CBFA efforts to expand conservation efforts, instead launching its own campaign to restrict logging in Canada’s Boreal forests. From the day after the CBFA was signed, Greenpeace began preparing for the damage control they thought might be necessary. (The audio here, obtained by the Vancouver Media Co-op, is of a conference call among Greenpeace staffers.) In fact, from the day the CBFA was signed, Greenpeace has been criticized from other environmental groups for selling out. This type of publicity may have had an impact on the organization’s financial situation.

Greenpeace’s Financials

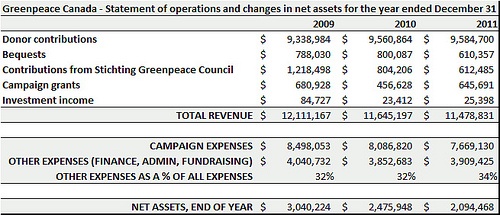

A look at the financial statements included in the Greenpeace audited financial statements show that while donor contributions have increased slightly, total revenue, total campaign expenses and net assets at the end of the year have all declined. As a result, expenditures on campaigns—the actual work of the organization—have been decreasing since 2009 and overhead—finance, administration and the cost of fundraising—now represent 34 percent of the organization’s costs.

Nothing is better for fundraising than the kind of confrontation that Greenpeace engaged in prior to the CBFA and for which is has been known since its inception. As one of Greenpeace’s co-founders, Patrick Moore points out, “You cause fear in the public, they give you money so you can take the fear away.”

That, of course, pre-supposes that “taking the fear away” is in the organization’s best interest. In the case of Greenpeace and many other environmental groups, trafficking in fear through confrontation increases donations.

The Heart of Greenpeace: Confrontation, Not Compromise

As Moore points out in Confessions of a Greenpeace Dropout, a book about his decision to leave the organization in the mid-80s:

“The real challenge was to figure out how to take the environmental values we had helped create and weave them into the social and economic fabric of our culture. This had to be done in ways that didn’t undermine the economy and were socially acceptable. It was clearly a question of careful balance, not dogmatic adherence to a single principle.

I knew immediately that putting sustainable development into practice would be much more difficult than the protest campaigns we’d mounted over the past decade. It would require consensus and cooperation rather than confrontation and demonization. Greenpeace had no trouble with confrontation—hell, we’d made it an art form—but we had difficulty cooperating and making compromises. We were great at telling people what they should stop doing, but almost useless at helping people figure out what they should be doing instead.

It also seemed like the right time for me to make a change. I felt our primary task, raising mass public awareness of the importance of the environment, had been largely accomplished. By the early 1980s a majority of the public, at least in the Western democracies, agreed with us that the environment should be taken into account in all our activities. When most people agree with you it is probably time to stop beating them over the head and sit down with them to seek solutions to our environmental problems.

At the same time I chose to become less militant and more diplomatic, my Greenpeace colleagues became more extreme and intolerant of dissenting opinions from within.

In the early days we debated complex issues openly and often. It was a wonderful group to engage with in wide-ranging environmental policy discussions. The intellectual energy in the organization was infectious. We frequently disagreed about specific issues, yet our ultimate vision was largely shared. Importantly, we strove to be scientifically accurate. For years this had been the topic of many of our internal debates. I was the only Greenpeace activist with a PhD in ecology, and because I wouldn’t allow exaggeration beyond reason I quickly earned the nickname “Dr. Truth.” It wasn’t always meant as a compliment. Despite my efforts, the movement abandoned science and logic somewhere in the mid-1980s, just as society was adopting the more reasonable items on our environmental agenda.

Ironically, this retreat from science and logic was partly a response to society’s growing acceptance of environmental values. Some activists simply couldn’t make the transition from confrontation to consensus; it was as if they needed a common enemy. When a majority of people decide they agree with all your reasonable ideas the only way you can remain confrontational and antiestablishment is to adopt ever more extreme positions, eventually abandoning science and logic altogether in favor of zero-tolerance policies.

And here, we get to the crux of the reason that Greenpeace (and other groups that operate like them) cannot be trusted. They are not interested in solving real problems, the ones that exist in the real world where the environment and social, economic and human needs meet. When it comes to making decisions, science and logic will always take a back seat to ideology. Good and reasonable solutions will always be shunted away in favor of the blind and unending pursuit of perfect ones.

Replace “Do Not Buy” with “Do Not Donate”

When Greenpeace signed the CBFA, it pledged it would discontinue its “Do Not Buy” campaigns against forest products companies and their customers. Based on Greenpeace’s untrustworthiness, in light of the fact that it opts for confrontation over solutions, and because $0.34 of every $1.00 it spends each year goes NOT to saving caribou or the Boreal forests but to overhead, perhaps it is time to take the advice of Peter Foster of the Financial Post and start a “Do Not Donate to Greenpeace” campaign. Those inclined to give money to save Boreal forests would be better off supporting organizations that continue to collaborate with forest products companies in support of the Canadian Boreal Forest Agreement.

Comments

04-08-2013

A few years ago former Secretary of Interior Stewart Udall confided in me, “I think we (he was speaking of the environmental movement) have gone too far. ” This article confirms that perspective.

Comments

06-19-2013

An excellent, dispassionate analysis of the irresponsible way that radical environmental organizations operate when dealing with forest products companies. Facts are unimportant. Unfortunately, the majority of concerned citizens don’t perceive the difference. As someone once said, you are allowed to have your own opinions but not your own facts. I would like to read what Ms. Kinney might say about the recent agreements between the Dogwood Alliance and International Paper.