3 min read

Forest Industry in Finland & Russia: Opportunities & Challenges

Vasylysa Hänninen : March 8, 2018

With a shared border, similar terrain and climate, tree species and growing seasons, Finland and Russia have dense forests and active forest industries that make use of them. However, a number of supply chain and operational differences exist between the two nations.

Due to its immense landmass, much of which is forested, Russia accounts for nearly 20 percent of the world’s standing forest resources. The forest standing stock in Russia is nearly 82 billion cubic meters (m3), and the standing stock in Finland is approximately 2 billion m3. (Global standing stock is roughly 434 billion m3.)

The Russian forest industry has traditionally been heavily oriented toward exports. While the national currency (ruble) was especially weak from the end of 2015 and through mid-2016 (as low as 76 RUB per 1 USD), the industry increased exports in order to maximize profits in its national currency. Supplementary revenues were then invested into capacity and greenfield expansions, as well as value-added products (birch plywood, coniferous sawmilling) that stimulated an increase in export demand.

Growing Climate & Harvesting

In both Finland and Russia, winter harvesting and forwarding windows have become shorter due to relatively mild winters and rainy summers over the last few years. This year in northwest Russia, mass forwarding only began at the beginning of January when roads were finally frozen over. Due to its more developed forest road infrastructure, harvesting and forwarding is typically carried out year-round in Finland.

However, both countries have faced separate challenges from Mother Nature in recent years: heavy storms with damaging winds have been a problem in Finland, and Russia is dealing with catastrophic wildfires.

Forest Management Practices

In Finland, sustainable and intensive forest management practices have long been a standard practice, and harvested stands are regenerated with coniferous species (pine or spruce, depending on the forest location, type, habitat, etc.). But just across the border in Russia, current forestry and silviculture policies require no more than 10% of stand regeneration after harvesting. Thinning is also not a common practice and competition between species and trees of different age classes is high.

The largest share of harvested forests in Russia is currently being regenerated naturally, which results in hardwood species—especially aspen—becoming dominant over coniferous species. This has created a real challenge because Aspen is not widely processed in Russia, as its quality is poor in early growth stages. Rather, the regional forest industry is driven by demand for coniferous pulpwood and sawlogs and birch veneer logs, but the yield of these products is usually quite low since regeneration practices are not the norm.

Imbalance between Supply & Demand

In Finland, roundwood consumption is in balance with supply, and it is also supplemented by imports (e.g., birch pulpwood from Russia and the Baltics region). Finland also widely uses low-value wood and forest residues for bioenergy production.

Based on the lack of forest management and the regional disparities in Russia, there is an imbalance between what is harvested in the forest and what is actively consumed via demand from the forest industry. For example, roughly 1.5 - 2 million m3 of high-value birch pulpwood is exported to Finland from regions close to the Finnish border. However, in some remote areas, birch and aspen pulpwood is simply left to decompose on the forest floor because the costs of extracting, transporting and then exporting this fiber are simply too high. Hence, the cost of products that are in high demand is not proportional to the harvesting volume from forest stands.

Infrastructure & Logistics Costs

In Finland, wood-consuming industries are concentrated in the central and southern parts of the country, and dense road networks also provide access to desolate and remote areas.

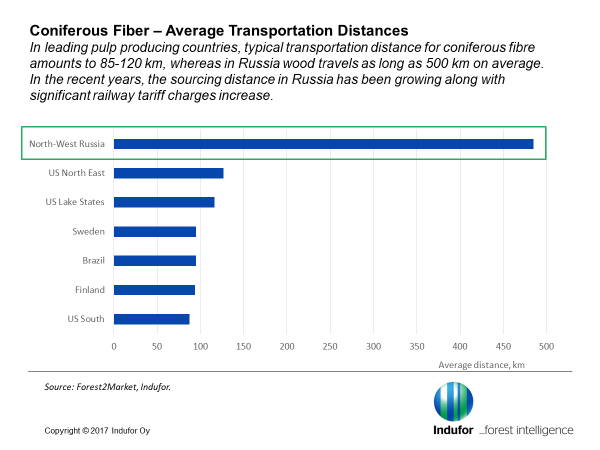

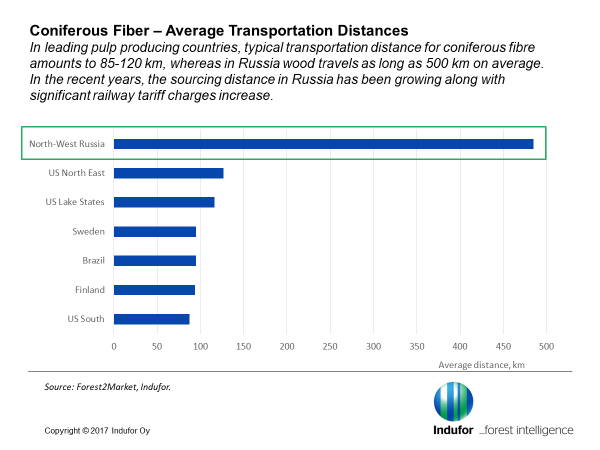

Russia, however, is notorious for its poor road infrastructure. Because timberland is leased for a maximum of 49 years, leaseholders do not wish to invest their own money into road construction and improvements. The State also has limited resources and is not willing to invest additional money into new roads; as a result, forests have been heavily harvested in close proximity to railway tracks, existing roads and waterways. Now, logging operations must go further and further away from transportation centers to gain access to marketable wood.

For this reason, transportation costs account for nearly half of current mill gate prices in Russia. Haul distances are long, railway tariffs have increased significantly over the last few years, and there is a major shortage of available railway cars.

Costs, Planning & Investment

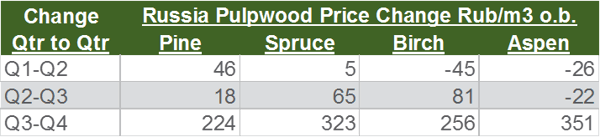

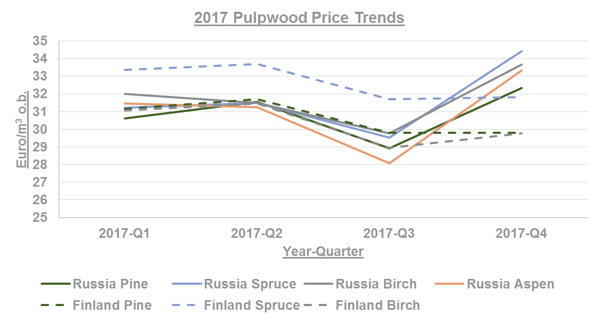

Roundwood prices in Russia increased significantly in local currency from 2016-2017. The most rapid increase was registered in the “European” part of Russia, namely the northwest and central regions closer to the border of Finland. This increase was seen across all species and product assortments—the most significant of which were birch logs and coniferous pulpwood and sawlogs.

While wood prices in Russia increased significantly in 4Q2017, no significant changes in wood prices in Finland were observed over the same time period.

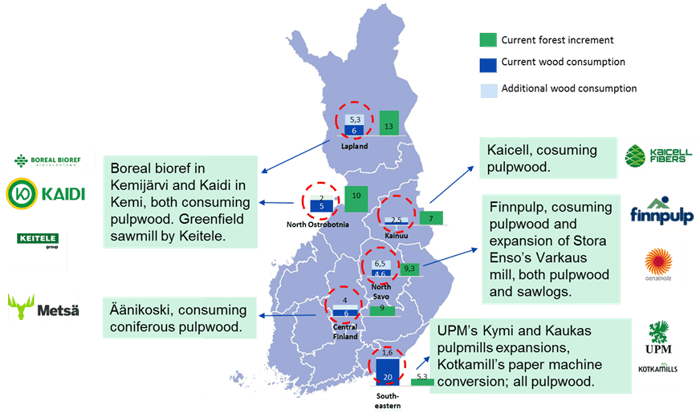

Because of the relative balance in supply and demand and the stable costs of wood, Finland is also home to a number of near-term scheduled investments and expansions across the forest supply chain (see map below).

At the same time, new investment and expansions in the Russian forest supply chain will face a number of challenges in the near term, including:

- A forest lease harvesting fee increase of 44 percent beginning in 2018.

- A possible export ban or limitation of Russian birch logs (a final decision from the government is still pending).

- Slow introduction of sustainable/intensive forest management practices in several regions of Russia, which does not incent new investment (as of now, only a pilot scale exists).

- Changes to the Russian forest code that will be implemented in 2018, which will likely increase regulatory schemes and deter new investment.

Finland and Russia may share a border and a number of geographic similarities, but the differences in the forest supply chains (and political environments) between the two nations is quite stark. While both countries have abundant, quality forest resources that support their respective forest products industries, the operational challenges facing the Russian industry are considerable.