5 min read

Housing Start Forecast: What the Next Five Years Really Look Like

Pete Stewart

:

November 2, 2018

Pete Stewart

:

November 2, 2018

Housing start forecasts are overly optimistic, with many in the industry suggesting we'll see 1.6 million housing starts in 2020. These estimates are overblown. Forest2Market’s current forecast for 2020 is 21 percent lower; here's why.

Demand—Millennial Buying Behavior

All the statistics point to pent-up demand from millennials. Several trends indicate that this cohort may not follow in the footsteps of their parents

- In general, millennials eschew the ownership of things. They stream music, film and television instead of buying CDs, DVDs and expensive cable TV packages.

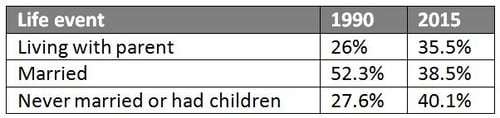

- Millennials are delaying major life changes that often lead to the decision to buy a home, like marriage and having children.

- Home prices are painfully high and interest rates are increasing. Millennials have more student loan debt than previous generations. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York reports that this debt totaled $1.4 trillion in 2018, up from $241 billion in 2003. With this debt comes two things that make loan qualification difficult: lower credit scores and high debt to income ratios. High down payments and mortgage payments are obstacles as well.

The 2008 housing collapse was a formative event for this generation, and they therefore have the lowest rate of home ownership in generations. According to the Urban Institute, millennials between 25-34 years old have a homeownership rate that is 8 percentage points below that of baby boomers when they were the same age and 8.4 percentage points below that of Generation X. Data from the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS), which includes U.S. Census and American Community Survey microdata from 1850 to the present, show that 32.3 percent of young people (25-35 years old) were homeowners in 2017, up just slightly from 2016 when it was 32.2 percent. This statistic hit a high of 55 percent in 1980 and was 45 percent prior to the Great Recession (2005). While 2016 and 2017 data show that the decline from 1980's high might have finally leveled off, the return to pre-recession buying behavior is unlikely.

When they do decide to enter the market, however, millennial buying behavior is not following the historical pattern of buying a starter home, living in it for 5-7 years, and then making a second purchase of a dream home. Instead, millennials are skipping starter home purchases, saving longer to amass larger down payments and making their first homes their dream homes. Ultimately, this cohort will buy half the number of homes in the beginning stage of their adult lives.

Supply—Labor, Land and Lumber

Labor

While the post-recession improvement in the employment numbers for the construction industry has been steady from 2011 through 2017, the number of unfilled construction jobs has been climbing in 2018. In August 2018, the number of open jobs in the sector increased to 298,000. This is 8.4% higher than July (275,000) and 38.6% higher than August of 2017. A recent survey conducted by Autodesk and the Associated General Contractors of America (AGC) found that 80% of responding contractors were having trouble finding skilled craft workers. Eighty-one percent expected it to continue to be hard, or become even harder, to find qualified new hires over the course of the next year. The national unemployment rate was 3.7% in September 2018, but the unemployment rate in the construction sector was 5.0%, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

The causes of this shortage are varied:

- Fewer young people are choosing construction as a profession and since the workforce is aging, retirees are not being replaced. The percentage of construction workers who are 24 or younger has declined nearly 30% from 2005 to 2016, according to BuildZoom. This is an issue that will continue to grip the industry.

- During the Great Recession, workers who lost their construction jobs found other jobs (mostly in the energy sector) and did not return to construction once home building picked up.

- The opioid crisis has exacerbated the labor shortage. A 2017 study conducted by Alan B. Krueger, the Bendheim Professor of Economics and Public Affairs at Princeton University, found a correlation between opioid prescription rates and the labor force participation rate. During the study period between 1999 and 2015, 20% of the decline in men's labor force participation could be attributed to opioid prescriptions.[i] More rigorous drug screenings have also led to more potential workers being turned away, and others who are otherwise qualified avoid drug tests by not applying for open positions.

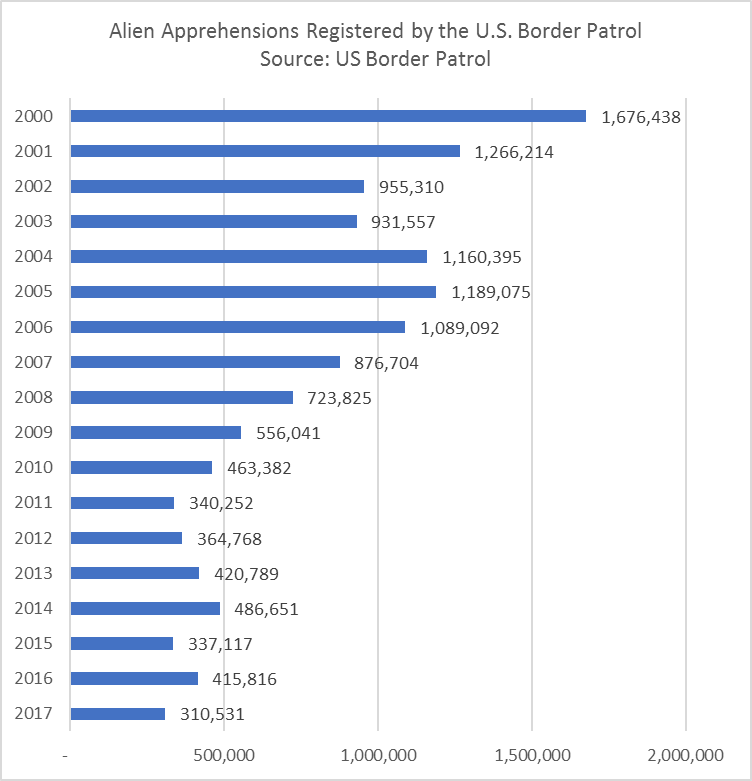

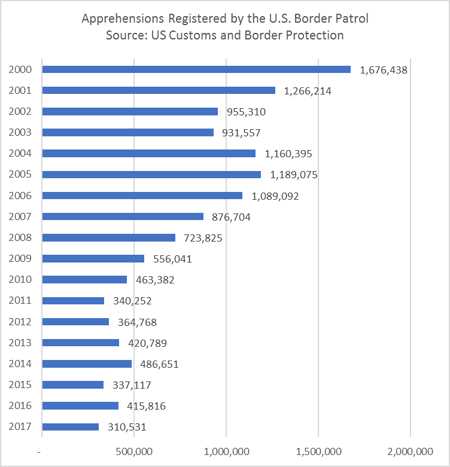

According to the Pew Research Center, nearly 15% of the workforce in the construction industry—roughly 1.25 million workers—are undocumented immigrants.[ii] A prime indicator of the scale of undocumented immigrants from Latin America is the number of people who are apprehended when attempting to cross the US–Mexico border. The data from the Border Patrol shows that that number of apprehensions in 2017 was the lowest it has been since 2000: 310,531.

According to the Pew Research Center, nearly 15% of the workforce in the construction industry—roughly 1.25 million workers—are undocumented immigrants.[ii] A prime indicator of the scale of undocumented immigrants from Latin America is the number of people who are apprehended when attempting to cross the US–Mexico border. The data from the Border Patrol shows that that number of apprehensions in 2017 was the lowest it has been since 2000: 310,531.- Two specific policies, if enacted, would reduce the number of immigrants working in construction legally:

- An estimated 10% of those with work permits issued under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program work in the construction industry; if the program is not renewed, 70,000 jobs would be added to the total number of unfilled construction jobs.

- Roughly 30,000 construction workers have work permits under the Temporary Protected Status they were granted when they sought asylum. If this policy is revoked, these workers would be deported.

The effect of this labor shortage is two-fold: it takes longer and costs more to complete a construction project. In fact, 69% of NAHB members reported that a worker shortage had caused delays in project completions. And a delay in completions means fewer houses can be built in a year, reducing the amount of inventory in the system.

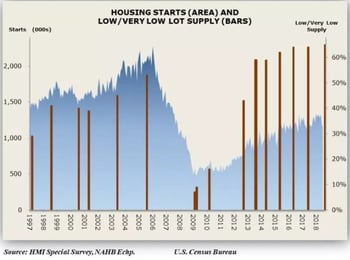

Land

Land shortages are also influencing the market. In urban areas, where demand is strongest, the availability of serviced, buildable lots suitable for residential construction is shrinking. In September 2018, the National Association of Home Builders found that 65% of builders reported that lot availability is low (43%) to very low (22%). This 65% is the highest low supply percentage reported since the NAHB began asking the question in 1997. Lot, and therefore home prices, are rising as a result.

Because land is a finite resource, this problem is likely to worsen.

Lumber

Another issue that could lead to shortages affecting the number of homes that can be built in the future is sawmill capacity. According to the Western Wood Products Association (WWPA), in 2017, total softwood lumber supply (domestic production and imports) was 47.565 BBF; WWPA also reports that just 32.35% of that amount, or 15.388 BBF, was used in residential construction. Forest2Market estimates that total softwood lumber supply in 2018 will be 48.39 BBF; 32.35% of that is 15.654 BBF.

Considering the average amount of lumber used to construct the average-sized US home, there isn't much room for housing starts to increase beyond their 2018 level of 1.266 million (Forest2Market’s estimate) before lumber shortages become common. With an additional 3.3 BBF of capacity coming on line between 2019-2021 (a 15% increase), the highest annual housing start level that US capacity will be able to absorb through 2021 is roughly 1.44 million units. And adding new capacity beyond 2021 will be limited to roughly 1.2 BBF a year, the limit to how much new sawmill capacity can be built in that amount of time.

At the most, therefore, if the maximum possible additional capacity is added each year and operates with the average operating rate for 2017 and 2018 of 87%, and if only 32.35% of that production is used in residential construction, approximately 32,000 new homes could be added to that total of 1.44 million units (that number would be closer to 100,000 units per year if 100% of the additional capacity were to go to residential construction). Improved operating rates and a larger percentage of production going into residential construction could raise these numbers.

Forest2Market's Housing Start Forecast

Because of headwinds facing both demand and supply, Forest2Market's current 2020 forecast for housing starts is 1.259 million units, roughly the same as it is for 2018 and 2019. In 2021, we anticipate the market will soften slightly to 1.209 million units, gaining back some ground in 2022 to 1.280 million units. In 2023, we should see a more dramatic recovery, with starts ranging between 1.55-1.80 million units from 2023-2028.

[i] Where have all the workers gone? An inquiry into the decline of the U.S. labor force participation rate